Structure

by Elvira Lindo

by Elvira Lindo

My passion for engineering, architecture, and construction in urban spaces dates back to my childhood, which was overshadowed by projects that shaped the history of my family.

Like each of the places where we ended up living, each member of my family is closely related to a project. I was born during the reconstruction of the Port of Cádiz, and our childhood photos all have a dusty background of soil and concrete. That was one of my great life lessons: an admiration for that which is yet to be, an insatiable curiosity about the process, and an awareness

that every construction project is the result of a design and that it involves many hands coming together, a huge physical effort, a sort of choreography that ranges from the drawing board to the manual trades. Those unforgettable experiences fueled my imagination: when I see a half-completed project, I try to visualize the system that it will become, and when I see a completed structure, I try to travel back in time, to the moment when it first took shape on paper.

Whenever I visit the Atazar Dam, where I spent four years of my childhood, I remember how the workers would pile into the trucks—standing room only—to be taken down to build what the engineers had designed. The wheels kicked up so much dust that it was impossible to see the trucks as they departed: it was like a John Ford movie, set against a backdrop of hope and personal dramas. Early every morning, my father would put on his hard hat, hop into the Jeep, and drive off to work. He loved the projects, and his enthusiasm always aroused my interest in the enormous effort being brought to bear.

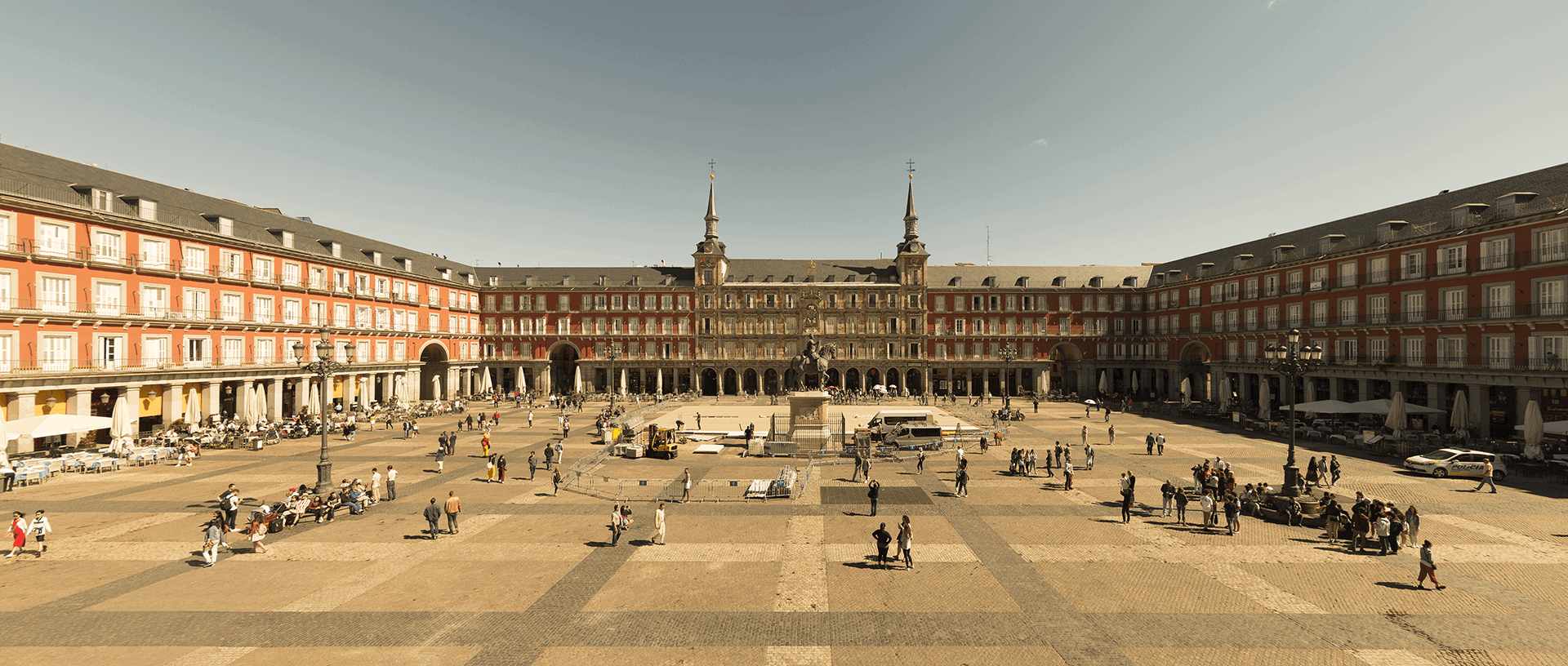

So how could I not be aware of the huge process involved when a new urban element or building is erected in a city? In these striking photos of Ferrovial projects by José Manuel Ballester, I can feel that energy of collective creation. It’s extremely difficult to simultaneously portray enormous structures and their detailed skeletons, the extraordinary traps that volumes set for the human eye. That’s something only an expert eye can achieve. Ballester introduces the viewer into the space, and I can imagine myself immersed in all those places that are so familiar to me; I know them—I’ve walked through most of them—because walking is how we turn the unattainable into the everyday.

There was a time when, in its supreme arrogance, architecture ignored—despised, even—what ought to be a core mandate for any creation that affects people’s lives: respecting the collective spirit, what Jane Jacobs called “social capital.” However, times have changed, and humanistic movements and the urgency of sustainability have made their mark.

We must find an equilibrium between construction and the interaction with human beings; though the latter may appear capricious and random, it embodies a deep and delicate wisdom

that it is advisable not to perturb. Markets, squares, museums, and theaters—all those buildings and meeting places designed to create bonds within the community fulfill their function better if they facilitate our coexistence. We citizens should not have to submit to crazy urban projects that force us to relinquish customs that have been ratified by the histories of our cities. Quite the contrary, construction in the city must take us into account, and consider each place’s culture and peculiarities, in order to ensure that cities are not merely insipid copies of the same template.

Functionality and beauty are not at odds, and it’s no secret that we behave better and more sociably in settings that are harmonious, accessible, and beautiful. We respect spaces that have been created to protect us from the elements. Repurposing buildings or industrial structures, restoring their beauty by giving them a facelift and so that they can rejoin day-to-day life in the city, is the real challenge of engineering and architecture today, and should always be guided by urban planning to generate pleasure and joy—the joy that creeps up on us unnoticed when we perceive the city as vibrant but also as helping us live. In all these cultural, commercial, and leisure buildings that Ballester has portrayed so skillfully, I see the quality that supports peaceful coexistence by the mass of individuals who make up the tremendous complexity that is humanity.

Elvira Lindo, Writer and Journalist

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 11 months 29 days 23 hours 59 minutes | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category ''Advertisement''. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months 29 days 23 hours 59 minutes | This cookies is set by GDPR Cookie Consent WordPress Plugin. The cookie is used to remember the user consent for the cookies under the category ''Analytics''. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-language | 11 months 29 days 23 hours 59 minutes | This cookies is set by GDPR Cookie Consent WordPress Plugin. The cookies will remember language preferences. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 12 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-non-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Non Necessary". |

| csrftoken | 11 months | This cookie is associated with Django web development platform for python. Used to help protect the website against Cross-Site Request Forgery attacks |

| lang | This cookie is used to store the language preferences of a user to serve up content in that stored language the next time user visit the website. | |

| PHPSESSID | This cookie is native to PHP applications. The cookie is used to store and identify a users' unique session ID for the purpose of managing user session on the website. The cookie is a session cookies and is deleted when all the browser windows are closed. | |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| wp-wpml_current_language | 1 day | Used by WPML to store language settings. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _csrf | Anti Cross-site request forgery cookie. | |

| _ga | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, campaign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assign a randomly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gat | 1 minute | This cookies is installed by Google Universal Analytics to throttle the request rate to limit the colllection of data on high traffic sites. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_5784146_31 | 1 minute | Google Used to distinguish users. |

| _gat_UA-141180000-1 | 1 minute | This is a pattern type cookie set by Google Analytics, where the pattern element on the name contains the unique identity number of the account or website it relates to. It appears to be a variation of the _gat cookie which is used to limit the amount of data recorded by Google on high traffic volume websites. |

| _gat_UA-20934186-10 | 1 minute | This is a pattern type cookie set by Google Analytics, where the pattern element on the name contains the unique identity number of the account or website it relates to. It appears to be a variation of the _gat cookie which is used to limit the amount of data recorded by Google on high traffic volume websites. |

| _gat_UA-5826449-38 | 1 minute | Used by Google Analytics to throttle request rate |

| _gat_UA-58630905-1 | 1 minute | Used by Google Analytics to monitor the rate of requests |

| _gat_UA-70491628-1 | 1 minute | This is a pattern type cookie set by Google Analytics, where the pattern element on the name contains the unique identity number of the account or website it relates to. It appears to be a variation of the _gat cookie which is used to limit the amount of data recorded by Google on high traffic volume websites. |

| _gcl_au | 2 months | Used by Google AdSense to experiment with advertising efficiency across websites using its services. |

| _gid | 23 hours 59 minutes | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the wbsite is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages viisted in an anonymous form. |

| _hjAbsoluteSessionInProgress | 30 minutes | This cookie is used to detect the first pageview session of a user. This is a True/False flag set by the cookie. |

| _hjCachedUserAttributes | Session | This cookie stores User Attributes which are sent through the Hotjar Identify API, whenever the user is not in the sample. These attributes will only be saved if the user interacts with a Hotjar Feedback tool. |

| _hjClosedSurveyInvites | 365 days | Hotjar cookie that is set once a visitor interacts with an External Link Survey invitation modal. It is used to ensure that the same invite does not reappear if it has already been shown. |

| _hjDonePolls | 365 days | Hotjar cookie that is set once a visitor completes a survey using the On-site Survey widget. It is used to ensure that the same survey does not reappear if it has already been filled in. |

| _hjid | 365 days | Hotjar cookie that is set when the customer first lands on a page with the Hotjar script. It is used to persist the Hotjar User ID, unique to that site on the browser. This ensures that behavior in subsequent visits to the same site will be attributed to the same user ID. |

| _hjIncludedInPageviewSample | 30 minutes | This cookie is set to let Hotjar know whether that visitor is included in the data sampling defined by your site's pageview limit. |

| _hjIncludedInSessionSample | 30 minutes | This cookie is set to let Hotjar know whether that visitor is included in the data sampling defined by your site's daily session limit |

| _hjLocalStorageTest | Less than 100ms | This cookie is used to check if the Hotjar Tracking Script can use local storage. If it can, a value of 1 is set in this cookie. The data stored in_hjLocalStorageTest has no expiration time, but it is deleted almost immediately after it is created. |

| _hjMinimizedPolls | 365 days | Hotjar cookie that is set once a visitor minimizes an On-site Survey widget. It is used to ensure that the widget stays minimized when the visitor navigates through your site. |

| _hjRecordingLastActivity | Session | This should be found in Session storage (as opposed to cookies). This gets updated when a visitor recording starts and when data is sent through the WebSocket (the visitor performs an action that Hotjar records). |

| _hjShownFeedbackMessage | 365 days | Hotjar cookie that is set when a visitor minimizes or completes Incoming Feedback. This is done so that the Incoming Feedback will load as minimized immediately if the visitor navigates to another page where it is set to show. |

| _hjTLDTest | Session | When the Hotjar script executes we try to determine the most generic cookie path we should use, instead of the page hostname. This is done so that cookies can be shared across subdomains (where applicable). To determine this, we try to store the _hjTLDTest cookie for different URL substring alternatives until it fails. After this check, the cookie is removed. |

| _hjUserAttributesHash | Session | User Attributes sent through the Hotjar Identify API are cached for the duration of the session in order to know when an attribute has changed and needs to be updated. |

| _smvs | 23 hours 59 minutes | Records visitor behavior data on the web. This is used for internal analysis and web optimization. |

| _uetsid | 1 day | This is a cookie used by Microsoft Bing Ads and it is a tracking cookie. Allows you to interact with a user who has already visited our website. |

| _uetvid | 2 weeks | Cookie installed by Google Tag Manager to store and track visits between sites. |

| apbct_visible_fields | Session | Prevents spam content |

| apbct_visible_fields_count | Session | |

| ct_checkjs | Session | Stores dynamic variables from the browser |

| ct_fkp_timestamp | Session | Stores visit time |

| ct_pointer_data | Session | Stores dynamic variables from the browser |

| ct_ps_timestamp | ||

| ct_timezone | Session | Stores visit time |

| dtCookie | Session | |

| GPS | 30 minutes | This cookie is set by Youtube and registers a unique ID for tracking users based on their geographical location |

| lumesse_language | 50 years ago | This cookie determines language of Application Process user interface (labels, interface etc.) |

| MR | 1 week | This cookie is used to measure the use of the website for analytical purposes. |

| smclient | 10 years | A cookie itself does not contain any information that enables to identify contacts and to recognize e.g. personal data of the website visitor. Connection to the contact card takes place in the SALESmanago system. |

| SMCNTCTGS | 10 years | A cookie contains tags assigned to hashed email in json {„hashedEmail”:”tag1,tag2″} |

| Smevent | 12 hours | A cookie contains eventId assigned after the event cart, deleted when the event purchase takes place. |

| smform | 12 months | Information about a form and pop-up behavior- a number of visits, a timestamp of the last visit, information about closing/minimizing pop-ups |

| smg | 12 months | Random ID in UUID format |

| SMOPTST | 10 years | A cookie contains contact status which is assigned to the hashed email in json {„hashedEmail”:”true”, „hashedEmail”:”false”} |

| smOViewsPopCap | 10 years | SM:X|, where X is replaced with a number |

| smrcrsaved | 12 months | True/false value |

| smuuid | 10 years | Unique ID – cookie itself does not contain any information that enables to identify contacts and to recognize e.g. personal data of the website visitor. Connection to the contact card takes place in the SALESmanago system. |

| smvr | 10 years | Values coded by base64 |

| smwp | 24 months | True/false value |

| test_cookie | 14 minutes | This cookie is set by doubleclick.net. The purpose of the cookie is to determine if the users' browser supports cookies. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _fbp | 2 months 28 days 23 hours 59 minutes | This cookie is set by Facebook to deliver advertisement when they are on Facebook or a digital platform powered by Facebook advertising after visiting this website. |

| everest_g_v2 | 1 year | The cookie is set in eversttech.net domain. The purpose of the cookie is to assign clicks to other events on the customer's website. |

| fr | 2 months 28 days 23 hours 59 minutes | The cookie is set by Facebook to show relevant advertisements to the users and measure and improve the advertisements. The cookie also tracks the behavior of the user across the web on sites that have Facebook pixel or Facebook social plugin. |

| IDE | 2 years | Used by Google DoubleClick and stores information about how the user uses the website and any other advertisement before visiting the website. This is used to present users with ads that are relevant to them according to the user profile. |

| lms_ads | 30 days | It is used to identify LinkedIn members from designated countries for advertising purposes. |

| mid | 9 years | The cookie is set by Instagram. The cookie is used to distinguish users and to show relevant content, for better user experience and security. |

| MUID | 1 year | Used by Microsoft as a unique identifier. The cookie is set using embedded Microsoft scripts. The purpose of this cookie is to synchronize the identifier in many different Microsoft domains to allow user tracking. |

| NID | 6 months | This cookie is used to a profile based on user's interest and display personalized ads to the users. |

| personalization_id | 2 years | This cookie is set by twitter.com. It is used to integrate the sharing features of this social network. It also stores information about how the user uses the website for tracking and targeting. |

| uid | 1 year | This cookie is used to measure the number and behavior of website visitors anonymously. The data includes the number of visits, the average duration of the visit on the website, the pages visited, etc. in order to better understand user preferences for targeted ads. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months | This cookie is set by Youtube. Used to track the information of the embedded YouTube videos on a website. |

| YSC | Session | This cookies is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos. |